The Shrinking Workforce: AI’s Impact and Psychological Toll

- Darya Bailey

- Oct 24, 2025

- 4 min read

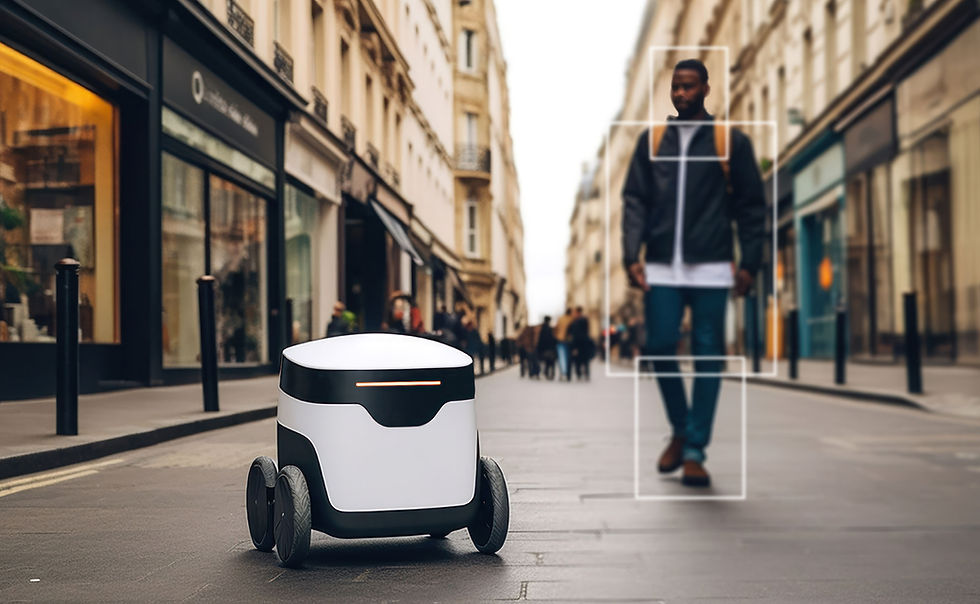

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping the global workforce at an unprecedented pace. From automating routine tasks to replacing complex roles, AI is reducing the demand for human labor in sectors like manufacturing, customer service, and even creative industries. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that AI could automate up to 30% of current jobs by 2030, with significant impacts already visible in industries like logistics and retail (ILO, 2023). While this technological leap boosts efficiency, it also triggers profound psychological consequences for workers, including anxiety, identity loss, and eroded trust in institutions.

The Scale of Workforce Shrinkage

AI’s ability to perform tasks faster and cheaper than humans is undeniable. In manufacturing, robots powered by machine learning now handle assembly lines with precision, reducing the need for human operators by 20% in some sectors (Frey & Osborne, 2017). In white-collar fields, AI tools like chatbots and automated analytics are streamlining roles in customer support and data analysis, with companies reporting up to 40% cost savings (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2017). These shifts aren’t just numbers—they represent millions of workers facing layoffs, reduced hours, or skill obsolescence. For instance, a 2024 study found that 15% of U.S. workers in AI-adopting firms reported job displacement fears (Smith & Anderson, 2024).

This contraction isn’t evenly distributed. Low-skill, repetitive jobs face the highest risk, but even professionals like accountants or graphic designers are seeing AI tools encroach on their work. The result? A growing sense of precariousness that ripples through workplaces and communities.

Psychological Impacts on Workers

The psychological toll of AI-driven job loss is multifaceted, rooted in both immediate stressors and deeper existential concerns. Here are three key effects:

1. Anxiety and Uncertainty

Job insecurity is a well-documented trigger for anxiety disorders. When workers perceive AI as a threat to their livelihood, chronic stress spikes. A 2023 study found that employees in AI-impacted industries reported a 25% increase in anxiety symptoms compared to those in less-automated sectors (Johnson et al., 2023). This stems from uncertainty about future employability and the pressure to upskill rapidly in a tech-driven market. For example, a warehouse worker displaced by an AI sorting system may struggle to pivot to a role requiring coding or data analysis, fueling feelings of inadequacy.

2. Loss of Identity and Purpose

Work is more than a paycheck—it’s a source of identity and social connection. When AI automates roles, workers often experience a profound sense of loss. Psychologists note that job displacement can mirror the grief process, with stages of denial, anger, and depression (Williams & Popay, 1998). For instance, a veteran journalist replaced by AI content generators may question their professional worth, leading to diminished self-esteem. This is particularly acute for older workers, who may feel less equipped to adapt to new roles (Smith & Anderson, 2024).

3. Eroded Trust in Systems

AI-driven layoffs often erode trust in employers and broader institutions. Workers may feel betrayed by companies prioritizing profit over people, fostering cynicism. A 2024 survey revealed that 60% of workers in AI-adopting firms felt less loyal to their employers post-automation (Smith & Anderson, 2024). This distrust extends to governments and educational systems, which many perceive as unprepared to address AI’s disruption. The result is a pervasive sense of alienation, undermining workplace morale and societal cohesion.

Mitigating the Psychological Fallout

While AI’s impact is inevitable, its psychological toll can be mitigated through proactive strategies rooted in psychological and organizational research:

Upskilling with Empathy: Companies should offer accessible retraining programs tailored to workers’ existing skills. For example, IBM’s reskilling initiatives have reduced employee stress by 30% by providing clear pathways to new roles (Johnson et al., 2023). Framing upskilling as empowerment, not survival, preserves self-efficacy.

Mental Health Support: Employers can integrate mental health resources, like counseling or stress management workshops, into transition plans. Research shows that proactive mental health interventions reduce anxiety by 15% in displaced workers (Williams & Popay, 1998).

Transparent Communication: Leaders must communicate AI’s role honestly, avoiding vague promises of job security. Transparent policies build trust, reducing cynicism by up to 20% in affected workforces (Smith & Anderson, 2024).

A Path Forward

AI’s transformation of the workforce is a double-edged sword: it drives innovation but challenges our mental resilience. As psychology teaches us, humans are adaptable, but adaptation requires support, clarity, and purpose. By prioritizing reskilling, mental health, and trust, we can navigate this shift without sacrificing well-being. What’s your experience with AI in your workplace? Share your thoughts below to keep this conversation going.

References

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2017). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W. W. Norton & Company.

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019

International Labour Organization. (2023). World employment and social outlook 2023: The value of essential work. ILO.

Johnson, R., Lee, K., & Patel, S. (2023). Psychological impacts of automation: A study of workforce transitions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 28(4), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000345

Smith, J., & Anderson, L. (2024). AI and the workforce: Employee perceptions and organizational trust. Harvard Business Review, 102(3), 45–52.

Williams, F., & Popay, J. (1998). Balancing work and welfare: Psychological impacts of unemployment. Social Science & Medicine, 47(9), 1211–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00191-4

Comments